I interrupt the regular programming of walking the hills, chasing Little Man, scolding the pug and cooking with my husband to talk for a moment about community. I want to talk about belonging somewhere, calling it home, embracing its flaws and standing up for a place…taking care of it.

No matter where you live in this country you’ve probably caught bits and pieces about the changes that are occurring in Western North Dakota due to new technology that allows us to extract oil from the Bakken and other large reservoirs that lay 10,000 feet below the surface of the land…the land where our roads wind, our children run, our farmers cultivate, our schools and shops sit. The land we call community. The land we call home.

For the people who exist here oil is not a new word. Neither is the Bakken. My county is celebrating its 60th year of oil discovery soon and its county seat isn’t even 100 years old. So you can imagine many long time residents of the small “boomtowns” you’re hearing about have had their hand in the industry at one point or another in their lifetime. Some have stories about finishing high school or returning home from college and working in the oil fields in the 1970s, moving up in industry, making their place, seeing it through the rough times and coming out on the other side as leaders and veterans of the industry.

Veterans of the industry like the ranchers and farmers in this area working to exist and tend to their land while the search for oil below their wheat fields and pastures carries on around them. During rough times, times when cattle prices were low, or the rain didn’t fall, some of those landowners have taken a second job driving truck or pumping for oil to make ends meet, to pay off some debt, to get their kids through college.

These people have served as members of the school board, city council, 4-H leaders and musicians in local bands. They have helped build up their main streets, keeping small businesses in business and the doors of the schools struggling with declining enrollment open. They’ve coached volleyball and cheered on their hometown football teams. They’ve helped a neighbor with his fencing, brought their kids along on cattle drives, drove the school bus to town and back every weekday, filled the collection plate at church and then helped rebuild its steeple.

These people continue this way to this day and I expect many in this generation, my generation, will be telling similar stories when it’s all said and done…stories that start with back breaking, 80 hour a week job and end in a life made.

A kind of life we are all living out here surrounded right now by oil derricks and pumping units and wheat fields and new stop lights and cattle and badlands. And I know you’re hearing about it. It’s big news in a tough economy–an oasis of jobs, opportunity and money in what some have come to refer to as “The Wild West” or “The Black Gold Rush.” It’s a story of hope, yes, but what we really like is the drama don’t we? We like to hear about the guy who came to North Dakota on a prayer only to live in his car in the Wal-Mart parking lot while he hunted for a job that allowed him to send money home to his wife and kids, or build a house, or a booming business. We like to talk over the dinner table about how the bars are full and the lines are long at the post office, about how a new building is going up and how the new stop lights and three lane highway is not doing enough to control the traffic.

We talk about how our lives are changing. I have been trying to wrap my mind around what this means for the place I have and always will call home. But the bottom line is that without this change, I probably wouldn’t be here to contemplate it at all.

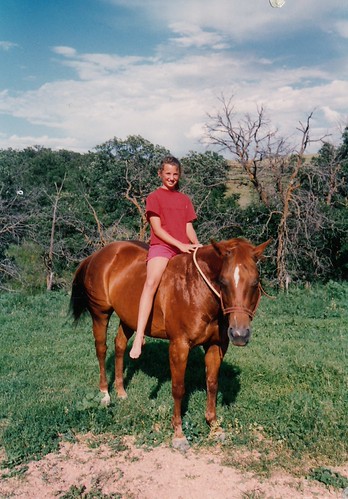

Yesterday I worked with a small group of elementary children who are full of life and love and energy and ideas…and nearly all of them have moved with their parents to this town within the last couple years. They come from all different backgrounds, from several states away. They come with ideas and insight into a world that extends outside this small and growing town where they now live. Some of them have left the only house they have known behind, some have left pets and horses they used to ride, wide open space and friends to live in a new place, a place much different from where they came from. A place that has work, but doesn’t have an abundance of houses their parents can chose from with big back yards where they can play.

When asked where they are from they will tell you Wyoming, California, Montana or Washington.

When asked about their home, they say it is here.

Change? Compared to these children, we know nothing of it.

Because last night I returned to the ranch after dropping off the last student only to pull on my tennis shoes and drive down the road with Husband to meet up with neighbors to play a few games of volleyball. And there we were at a small, rural recreation center surrounded by some of the community members who raised funds to build the place nearly fifteen years ago. Fifteen years ago when the pace was slower, but the most important values were there.

The value of having a space to get together to play a game, to craft, to hold meetings and New Years Eve parties and baby showers. In that very gym where I skidded across the floor last night to hit a volleyball my neighbor passed to me was the very gym I served pancakes in as part of a youth group fundraiser when I was twelve years old. It was where I gathered with friends and family after a community member’s funeral. It was where I attended 4-H meetings and put on talent shows with my friends. And it’s where I’m going to craft club next Tuesday. Yes, nearly fifteen years after that talent show this is still my meeting place and I still get to call all of the teachers, ranchers, accountants, stay at home moms, business owners and yes, oil industry professionals who are running after fly volleyballs, laughing and joking and skidding across the floor, my neighbors.

But you know what I need to remember? Those students and their families and the people who are on their way here to look for a better life? They are my neighbors too. And they have a lot to teach us.

So if you ask me how life has changed, I might tell you about the traffic. I might tell you how there are a couple oil wells behind my house and how that was hard to get used to. I will tell you about the new business coming to the area and how we now have stop lights in town. I will tell you about the challenges. And then I will tell you about the people who are keeping their fingers on the pulse of this development and discovery. I will tell you about those who are asking the right questions about our environment and making the tough decisions about our infrastructure in order to better accommodate new students in our schools and new residents of our towns so that they feel they belong here the same way I belong.

They are on the front lines welcoming visitors to the museum, taking the time to ask questions at the grocery store, spending their retirement as County Commissioners, City Council and Chamber of Commerce members. I will tell you about the people who are not only sticking it out during these growing pains, but who are working every day to make their home a better home for the next generation.

Yes, right now our community is overwhelmed. Whether or not we saw this coming, whether or not we thought we were prepared, many days for many people it feels like the phone calls, the needs that can’t be met, the questions that don’t have answers yet, are overwhelming…and it’s tempting for many to pack up and leave a place they don’t feel they recognize anymore.

But here’s what I’m proposing to those living in the middle of the Wild West and to those in any community really:

Stand up for it. Go to meetings. Ask questions. Play Volleyball together. Exist in it. Don’t be afraid to be frustrated, but then do something. Anything. Invite a new person to your quilting club. Put on a talent show. Volunteer. Attend a basketball game. Mentor a student. Instead of complaining about the trash in the ditches, get your friends together to pick it up. Set a good example. Set your standards and then be prepared to put your muscles into it.

If it’s your community, make it your priority. Because it’s your community and it’s worth loving and fighting to take the frustrations and turn them into solutions. To turn the complaining into action. To shift from fear and uncertainty to a place of positive energy and open-mindedness.

It isn’t easy, but those who have seen this through, those who have walked the main streets when the stores are full only to turn around to see them empty, those who built that school, owned that store, lived in that house for 50 years, they will tell you, not only is it worth the effort, it’s our responsibility.

Want to keep up with what’s happening in Western North Dakota and my hometown?

Visit: mckenziecounty.net for the latest in news and progress and the North Dakota Petroleum Council for information on North Dakota’s oil industry.