My favorite thing is the sound of little voices at Christmastime, singing out without restrain and all the confidence and innocence only a child holds. “Jingle Bells” and “Rudolf” sound the best when sung standing up in the bleachers of the elementary school gym, or on risers under lights at the holiday program. These songs were made to be sung by kids with boogers plugging their tiny noses, dressed in itchy sweaters and floofy skirts with at least one kid getting so entirely in the spirit of things with his dance moves that all eyes are inevitably on him, as they should be.

My favorite thing is the sound of voices together in a little country church after the lights have been dimmed and we have successfully lit one another’s candles without starting anyone’s hair on fire. Your dad and mom make a sandwich of you and your sisters and maybe your gramma and grampa, aunts and uncles and cousins are within arm’s reach, if you’re lucky and need another lap to sit on. Your best friend is across the room with her family too and her hair’s fixed in curls and she looks beautiful, and so do you and we all know the words to “Silent Night” and so you sing together with confidence, and love and gratefulness and it feels like peace.

My favorite is wondering if the magic of Santa could truly be real and if you could hear the reindeer on the roof if you stayed up late enough and listened. My favorite is believing the story that your grampa told you of the hoofprints he found on the front lawn when he was a kid. And the bites those reindeer took out of the carrots you left, and the cookies you baked and frosted with your mom you’ve set out with the milk, even when you’ve grown old enough to know better, you do it anyway, for your parents and little sister, and maybe, just in case.

My favorite is throwing the horses and cattle a few extra scoops of grain or cake in the crisp morning of the holiday and how, in some way, it always feels like those animals know it’s a special day too.

My favorite is the smell of caramel rolls when you come in with the cold on your coat, shaking off the snow, stomping your boots, your husband or your dad switching from work clothes to town clothes to stay in for the day….unless there is snow for sledding later. Then we’ll all go out again and then that is my favorite, because on Christmas we all to go the hill. On Christmas, even mom and gramma take a turn down.

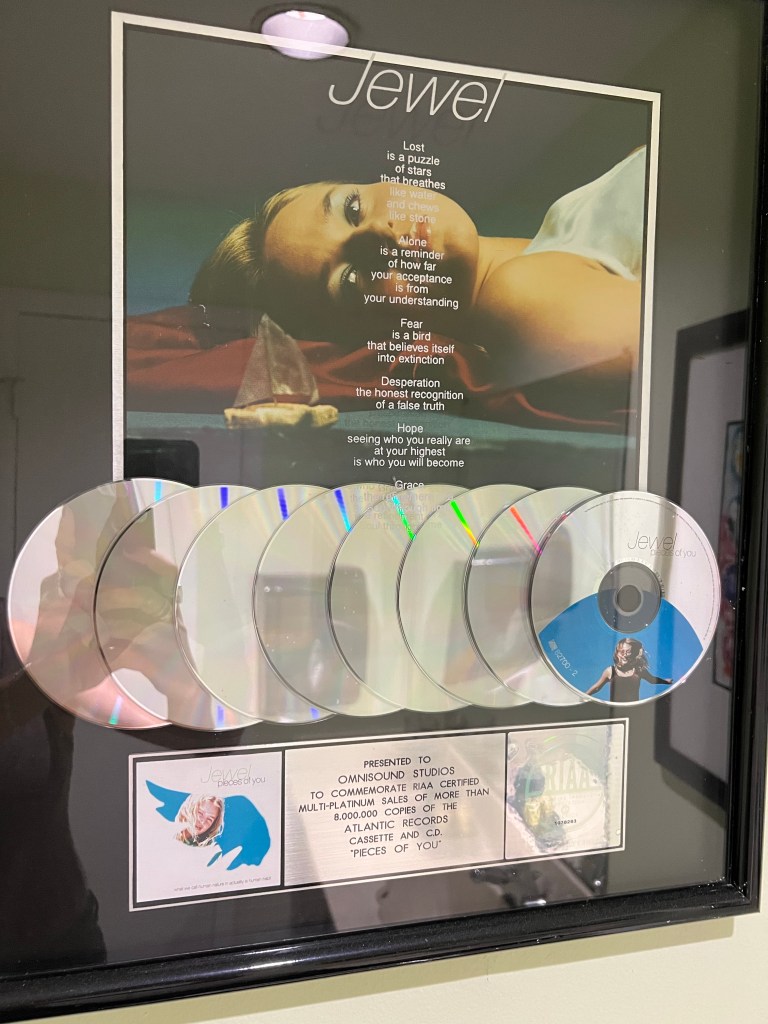

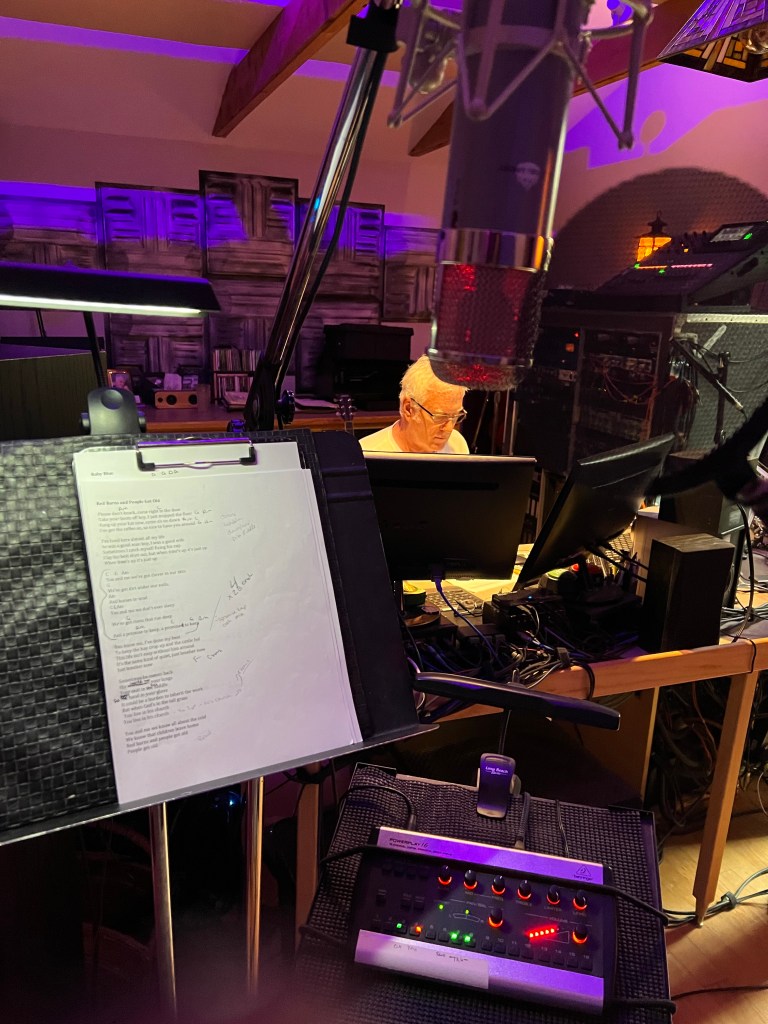

My favorite is the prime rib dinner served on the good dishes from the old buffet in the living room. And I like the broccoli salad the way mom does it, and I like to make the cheeseball in the shape of a snow man and everyone makes a fuss over it because there has to be a cheeseball in the shape of something or it’s not Christmas. My favorite is the sound of my dad’s guitar in the living room after the dessert has been served and we’re all full and sleepy and he asks the grand kids to sing along and he chooses “Go Tell in on the Mountain” just like we sang in Sunday School when he was young and we were young and you get a little lonesome for a time and place you can only go again because of the music. My favorite has always been the music. My favorite has always been the songs…