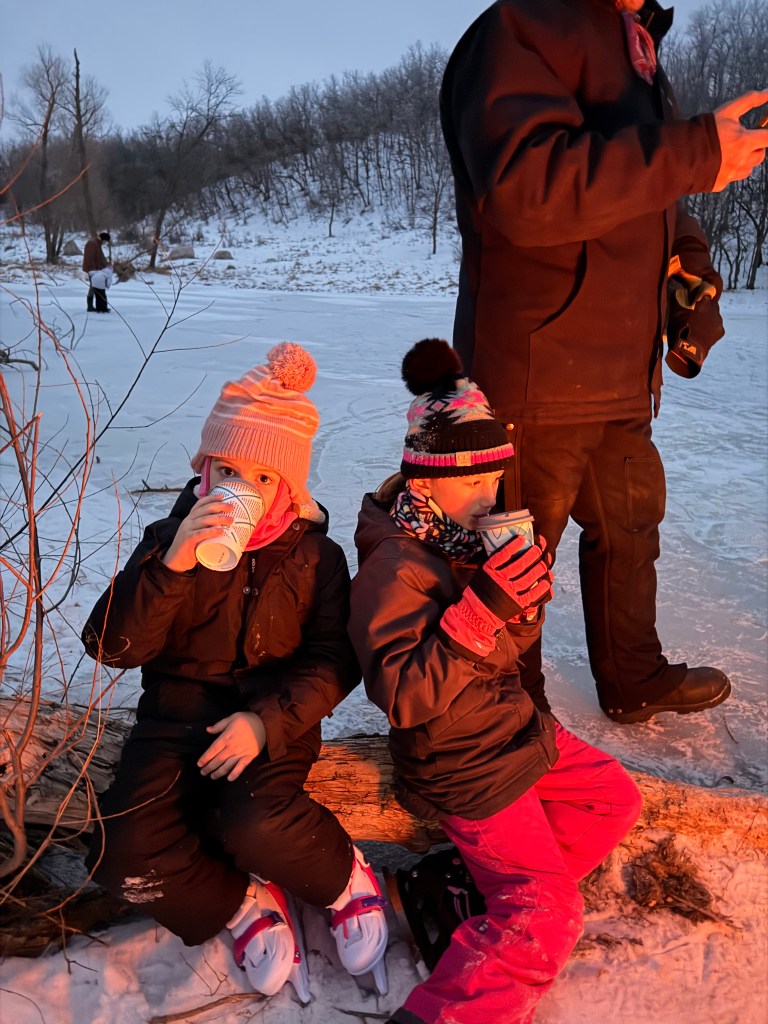

It’s March now, and I feel the chilled surrender that January brings start to break up and separate inside of me, even as I stand under a gray sky that blends into the horizon as if it weren’t a sky at all but a continuation of the snowy landscape…below us, above us…surrounding us.

Flakes fell from that sky yesterday afternoon, big and soft and gentle they drifted down to the icy earth and coaxed me from behind my windows to come outside and stick out my tongue.

When the snow falls like this, not sideways or blowing or whipping at our faces, but peaceful and steady and quiet, it’s a small gift. I feel like I’m tucked into the mountains instead of exposed and vulnerable on the prairie. I feel like, even in the final days before March, that someone has shaken the snow globe just the right amount to calm me down and give me some hope for warmer weather.

When the snow falls like this, I go look for the horses. I want to see what those flakes look like as they settle on their warm backs, on their soft muzzles and furry ears. I trudge to the barnyard or to the fields and wait for them to spot me, watching as they move toward that figure in a knit cap and boots to her knees, an irregular dot on a landscape they know by heart.

I know what they want as they stick their noses in my pockets, sniff and fight for the first spot in line next to me. I know they want a scratch between their ears.

I know they want a bite of grain.

They know I can get it for them.

Our horses in the winter take on a completely different persona. The extra layer of fur they grow to protect them from the weather makes them appear less regal and more approachable.

Softer.

I like to take off my mitten and run my fingers through that wool, rubbing them down to the skin underneath where they keep the smell of clover and the warmth of the afternoon sun. I like to put my face up to their velvet noses and look into those eyes and wonder if they miss the green grass as much as I do.

On this snowy, gray, almost March afternoon the horses are my closest link to an inevitable summer that doesn’t seem so inevitable under this knit hat, under this colorless sky.

I lead them to the grain bin and open the door, shoveling out scoops of grain onto the frozen ground. They argue over whose pile is whose, nipping a bit and moving from spot to spot like a living carrousel. I talk to them, “whoah boys, easy” and walk away from the herd with an extra scoop for the gelding who gets bullied, his head bobbing and snorting behind me.

In a month or so the ground will thaw and the fur on the back of these animals will let loose and shake off, revealing the slick and silky coat of chestnut, white, deep brown, gold and black underneath. We will brush them off, untangle their manes, check their feet and climb on their backs and those four legs will carry us over the hills and down in the draws and to the fields where we will watch for elk or deer or stray cattle as the sun sinks below the horizon.

I move my hand across the mare’s back, clearing away the snowflakes that have settled in her long hair and I rest my cheek there, breathing in the scent of hay and dust and warmer days.

She’s settled into chewing now, his head low and hovering above the pile of grain I placed before him. He’s calm and steady so I can linger there for a moment and wonder if he tastes summer in the grain the same way I smell it in her skin.

My farewell to winter is long, lingering and ceremonious.

But it has begun. At last, it has begun.